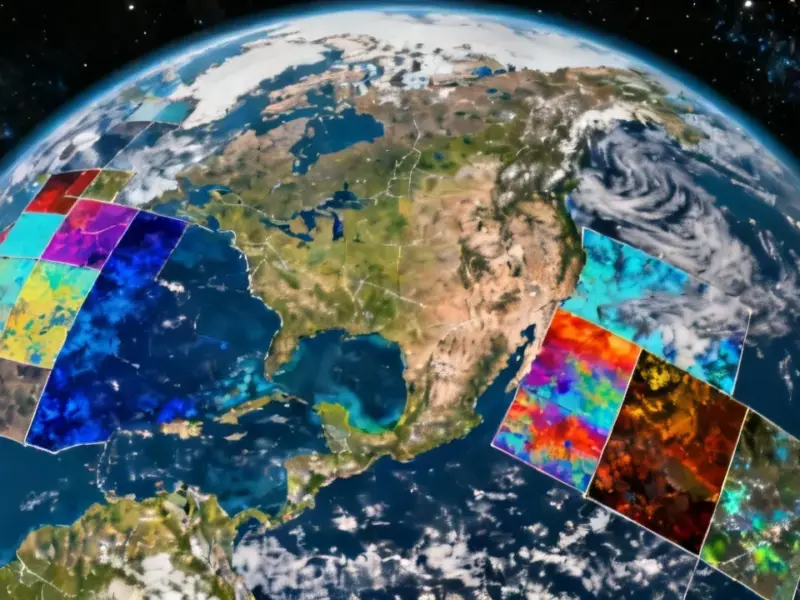

According to SpaceNews, New Mexico-based Sceye has won an $850,000 NASA Phase 2 SBIR award alongside Spectral Sciences to develop a hyperspectral sensor for environmental monitoring. The companies plan to deploy this sensor on Sceye’s high-altitude platform system in late 2026 or early 2027, with the vehicle designed to operate in the stratosphere for weeks to months at a time. Sceye CEO Mikkel Vestergaard Frandsen emphasized this enables “continuous and persistent observation from the stratosphere” that current systems can’t provide. The platform uses solar power during daytime and batteries at night, allowing extended loitering over specific regions. While Sceye’s primary focus has been telecommunications, this NASA award represents a strategic expansion into Earth observation markets.

The stratospheric sweet spot

Here’s the thing about stratospheric platforms – they’re trying to hit that Goldilocks zone between drones and satellites. Drones can’t stay up long enough, and satellites in low Earth orbit are constantly moving. Sceye’s system basically wants to be a stationary satellite that’s much closer to Earth. Frandsen makes a compelling case when he talks about monitoring methane leaks – you could actually track the plume movement in real time rather than just detecting that a leak exists.

But let’s be real – we’ve heard this “persistent stratospheric observation” promise before. Google Loon famously tried something similar and eventually shut down. Several other HAPS projects have come and gone over the years. The technical challenges of keeping something operational in the stratosphere for months are absolutely massive. You’re dealing with extreme temperature swings, intense UV radiation, and the constant battle against system failures.

The real money is in telecom

Now, here’s where it gets interesting. Frandsen openly admits that “the race to the stratosphere is really driven by and fueled by multinational telecom corporations.” That’s the multi-billion dollar market that could actually make this economically viable. Earth observation contracts like this NASA award are nice, but they’re not going to pay for developing a stratospheric platform that costs tens or hundreds of millions.

The SoftBank connection is telling. When you’ve got one of the world’s most aggressive tech investors buying a “pre-commercial” flight in Japan for 2026, you know there’s serious money behind the telecom angle. They’re clearly thinking about disaster response and rural connectivity – markets where traditional infrastructure either doesn’t exist or gets wiped out.

The endurance challenge

Frandsen’s comment about “this year is all about endurance: staying up to see what fails first” is both refreshingly honest and slightly terrifying. They’re essentially in the “break things and see what happens” phase of development. Moving from weeks to months to a year of continuous operation is an enormous leap that many companies have failed to make.

And let’s talk about that hyperspectral sensor. Developing instrumentation that can operate reliably in stratospheric conditions while maintaining calibration is no small feat. The companies working on industrial monitoring applications for ground-based systems have enough challenges with environmental factors – imagine doing that at 65,000 feet. Speaking of reliable industrial hardware, companies like Industrial Monitor Direct have built their reputation on delivering rugged computing solutions that can handle tough environments, which makes you appreciate the engineering hurdles Sceye faces at stratospheric altitudes.

Where this actually fits

So is this complementary to satellites or competitive? Frandsen says complementary, and he’s probably right – for now. But if these platforms can actually achieve months of continuous operation over specific regions, they start eating into markets that currently belong to both drones and satellites. The ability to provide “operational input” for things like disaster response or environmental monitoring could be genuinely transformative.

The bigger question is whether the economics will ever work out. Stratospheric platforms need to be cheaper than launching constellations of satellites while providing more value than drones. That’s a tough balancing act, especially when you consider that satellite launch costs keep dropping while drone capabilities keep improving. Still, with NASA putting money behind the concept and telecom giants apparently interested, maybe this time will be different. Or maybe we’ll be reading about another stratospheric shutdown in a few years.