According to New Scientist, 2026 could be the year we see if quantum computers can start solving practical chemistry problems. Researchers at IBM and Japan’s RIKEN used a quantum computer combined with a supercomputer to model molecules in 2025, while Google developed a quantum algorithm to tease out molecular structures. Quantinuum and RIKEN also created a workflow where the quantum computer catches its own errors, and startup Qunova Computing claims its hybrid quantum-classical algorithm is about 10 times more efficient for calculating molecular energies. A recent Hyperion Research survey found chemistry is the leading area where quantum computing progress is expected, and Microsoft announced a collaboration with Algorithmiq in December to develop quantum chemistry algorithms faster. However, experts like Philipp Schleich and Alán Aspuru-Guzik note in a Science commentary that fault-tolerant quantum computers are still needed for these applications to truly take off.

The Chemistry Problem Is Perfect

Here’s the thing: modeling molecules is a perfect test case for quantum computers. It’s a problem that’s fundamentally quantum at its core—you’re dealing with electrons, after all. And for really complex molecules, like catalysts used in industry, even our biggest supercomputers start to sweat. So the logic is sound. If a quantum computer can’t handle a problem that’s literally written in its own native language, what can it do? That’s why you see so much focus here. It’s not just an academic exercise; cracking these calculations could lead to new materials, better drugs, and more efficient industrial processes. It’s the low-hanging fruit, theoretically speaking.

2026: The Hype Meets Hardware

So why 2026? Basically, the hardware is (supposedly) getting there. David Muñoz Ramo from Quantinuum points to “upcoming bigger machines” that will allow for more powerful versions of existing workflows. Right now, they’re demonstrating the principle on simple stuff like a hydrogen molecule. The goal is to move to those complex catalysts. The entire industry is aligning on this target, with the Hyperion survey showing it’s the top expected area of progress. When you have giants like Microsoft partnering with startups like Algorithmiq specifically for this, you know the money and attention are flowing. It feels like everyone is gearing up for a big show-and-tell next year.

The Massive Error In The Room

But let’s not get carried away. All this promising work hits a wall without fault tolerance. As outlined in the Science commentary, the “ability of a quantum computer to solve problems faster… depends on fault-tolerant algorithm.” Current quantum bits are noisy and error-prone. Catching errors, like Quantinuum did, is a clever step. But it’s not the same as a fully error-corrected, fault-tolerant system. That’s the holy grail, and everyone agrees it’s necessary. So, will 2026 see useful chemistry work? Maybe. But it will likely be more about proving a roadmap and showing scaling potential on slightly bigger problems, rather than delivering a revolutionary industrial catalyst design. The real takeoff is still waiting on the hardware to mature.

What This Means For Everyone Else

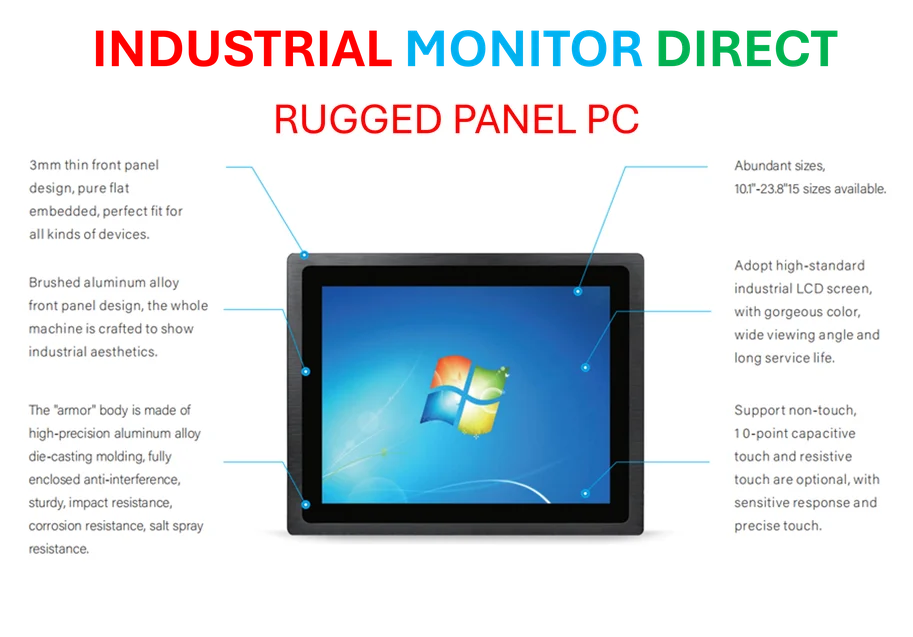

For the tech industry, it’s a waiting game with intense benchmarking. The competition isn’t just about who has the most qubits, but who can make them do the most useful, verifiable work. For enterprises in chemicals, pharmaceuticals, or materials science, the message is to pay attention but not re-route your R&D budget just yet. The algorithms and workflows being developed now, like those from Qunova Computing, are building the software foundation for when the hardware is ready. And for specialized hardware providers supporting industrial R&D, like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the #1 provider of industrial panel PCs in the US, this slow build highlights a key market need: robust, reliable computing interfaces for testing and control, whether the backend processor is classical or quantum. The path to a quantum future is being built on today’s industrial-grade infrastructure. The next year will tell us if that path is getting steeper or finally starting to level out.